Building the Infrastructure for Community-Led Change: Why we need know-how, now

We're at a critical moment for place-based change in the UK. Major funding programmes are launching across the country - Pride in Place, Neighbourhood Health, Community Wealth Funds, and others - designed to put power and resources directly into the hands of local people. This represents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to tackle persistent disadvantage in our most struggling communities.

But there's a hard truth we need to face: money alone won't deliver the change we need.

The Challenge: Communities That Are Stuck

The data tells a stark story. Analysis of Indices of Multiple Deprivation shows that our most disadvantaged communities are stuck in a cycle of deprivation. According to the Independent Commission on Neighbourhoods, 82 per cent of neighbourhoods currently in the most deprived 10 per cent were in the same situation six years ago. We're seeing extreme disadvantage sitting next to growing wealth, with some communities scoring so poorly across all measures that the task of designing and delivering change seems overwhelmingly difficult.

The issues local people care most about: health, opportunity, safety, and belonging, are complex, interlinked, and long-standing. They're not problems with quick fixes, yet our current approach to funding isn't addressing them effectively.

Research from the Independent Commission on Neighbourhoods reveals a troubling pattern: average grant funding per head in England is £12.23, but in the most deprived communities, those considered to be doubly disadvantaged, it's just £7.77. According to NCVO, despite overall funding for the voluntary and community sector growing by 41% in real terms over the last decade, small local organisations (those with annual revenue under £100k) received less than 3% of that growth.

In short, funding and impact are not reaching the places or organisations best positioned to lead deep, systemic change.

The Missing Piece: Local Change Infrastructure

If communities are to make the most of these emerging opportunities, we urgently need to build what we call local change infrastructure. This isn't about buildings or bridges, though these matter too, but about the capacity to enable collective action.

Think of it as building a coalition of the necessary skills, leadership, relationships, and coordination that enable people who live and work in a place to work together effectively over time. Some of this capability already exists in every place, but many communities need and want support to build the capabilities that help them use today's funding well and leave behind a lasting legacy of local leadership and sustained change.

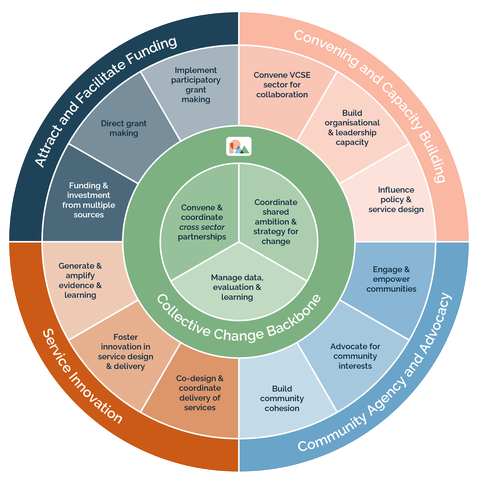

Drawing on our work across the UK and learning from international practice, we've identified five core functions that strong local change infrastructure needs to provide:

- Convening and capacity building: Connecting local partners to collaborate around priorities, creating leadership skills and mindsets across partners to enable collaboration, and creating spaces and opportunities for partners and the community to influence policy and service design.

- Community agency, advocacy and cohesion: Creating a positive narrative around the potential of the place, building community capacity to participate as partners in change, and enabling communities to influence the change they want to see.

- Attracting and facilitating funding: Building business cases and grant applications to bring in funding and investment to back shared ambitions for change, potentially including distributing funding directly.

- Service innovation, evidence and learning: Co-designing and commissioning evidence-backed interventions, testing and learning new ideas, generating and sharing evidence and learning to enable adaptation and improvement.

- Collective change backbone: A coordinating capability that connects and enables collective action around a shared ambition for change.

The ‘Backbone’ Function

At the heart of this infrastructure is what's often called the Collective Change Backbone, the coordinating capability that turns shared ambition across policy priorities into sustained action. This provides both the capacity and capability for local change, and our view is that building this backbone function is a priority right now.

What makes the backbone role unique is that it is responsible for creating an effective 'container for change,' nurturing the conditions in which trust, collaboration, and learning can take root. It's about building relationships, supporting boards and partnerships, enabling meaningful participation through working groups, citizen assemblies, and youth forums, and holding the long-term focus when others are pulled toward short-term pressures.

This role requires a rare blend of skills: technical and relational, analytical and human, directive and facilitative. Strong backbone teams are trusted locally, ideally independent of vested interests, comfortable with conflict, and committed to learning. They convene the people, organisations and sectors across a place to shape a shared ambition, design governance that genuinely shares power and centres community agency, shape narratives of pride and belonging, and grow future leaders.

A collective change approach creates a platform for place-wide work, building interventions around local priorities, whether that's mental health, youth crime, or early years development. It creates a route for large and small organisations to contribute at different levels, engages funders as strategic partners, and ensures the community has significant and lasting input into key decisions that will most impact them.

Different Starting Points, Shared Purpose

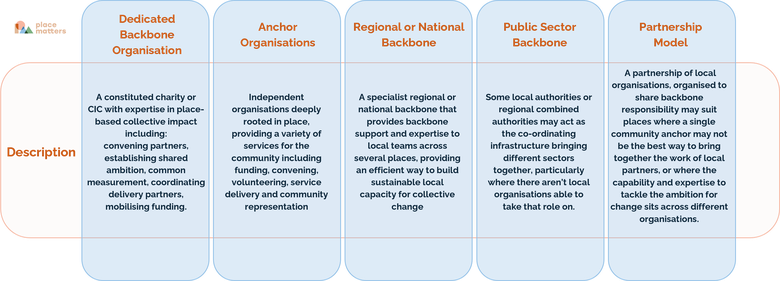

There's no single model for this change infrastructure. The backbone function can take different forms depending on local assets, capabilities, and ambitions. It's best understood as a function rather than simply an organisation, one that can be created in different ways and evolve as a locality's capability changes.

Over the years, we've seen several different models emerge, each with strengths and limitations:

Dedicated backbone organisations have deep expertise in coordinating place-based work, evidence-based practice, and fundraising power. Often national organisations working in place for a defined period, they bring strong track records and the ability to mobilise significant resources. Examples include Right to Succeed and Thrive at Five. The challenge is sustainability and building a lasting local legacy when the organisation eventually moves on.

Community anchor organisations have deep roots and legitimacy within their communities. With support to develop leadership skills, evidence-informed practice, and power-sharing governance, many can grow into the full coordinating role. These might be community and voluntary councils, local infrastructure organisations, community foundations, local charities, community businesses, education providers, or purpose-led organisations like housing associations. Their strength lies in their long-term commitment to place and existing relationships, but many do not currently have the capacity and capability to carry out the backbone role

Regional/national backbone models combine local anchors with specialist support across multiple places. Canada's Building Youth Futures programme demonstrates this approach well, with local backbone teams having dual accountability to both a local anchor organisation and a national backbone team. This reduces short-termism while strengthening quality, though governance can be more complex. To our knowledge, this model has not yet been tested in a UK context.

Public sector backbones can work where local authorities or regional combined authorities are trusted catalysts. However, this is often challenging due to power imbalances, capacity constraints, and limited trust among communities in local government bodies.

Partnership models distribute the backbone function across organisations, building distributed leadership but adding complexity around accountability and decision-making. This can work well when no single anchor is best placed to lead, or when high-quality local capability exists across different organisations, though it adds some additional complexity.

The bottom line: places must build on the assets they already have. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to supporting systemic change, and many ways to build the capability for community-led change.

What It Really Takes to Lead

Leading a backbone team isn't just coordination; it's deeply relational work. You're constantly brokering relationships across community groups, councils, funders, and services. Creating safe spaces for difficult conversations. Building trust slowly. Hearing hard truths.

You're weaving together people with different identities, interests, and histories, often shaped by inequality and past failures. Without real relationships, collective action simply doesn't happen. The role carries real tension: you must be neutral, serving the whole place equitably, while also disrupting entrenched systems. Political astuteness isn't optional. You need to understand local power dynamics, when to push forward and when to pause.

You mediate competing agendas, make difficult calls, and hold uncertainty, often without recognition. Because success is collective, individual acknowledgement is rare. You carry others' hopes and frustrations alongside your own. When poorly supported, this leads to burnout. When well supported, it's profoundly meaningful work.

One key lesson from Big Local is that more can be done upfront to build residents' skills and confidence to lead. Communities often stay stuck because no one is holding the whole, aligning effort, and nurturing the relationships needed for shared action.

Investing in local change infrastructure isn't overhead; it's the foundation that enables transformation.

Building the Capability Communities Need

The success of government and philanthropic funding in communities depends on quickly and at scale strengthening local change infrastructure, responding to the maturity of existing capabilities with packages of support that build on existing strengths and assets.

We consistently hear that people want to learn from others facing similar challenges. They want shared, accessible language and helpful tools and frameworks. They want peer-led support from those with experience and understanding of their context.

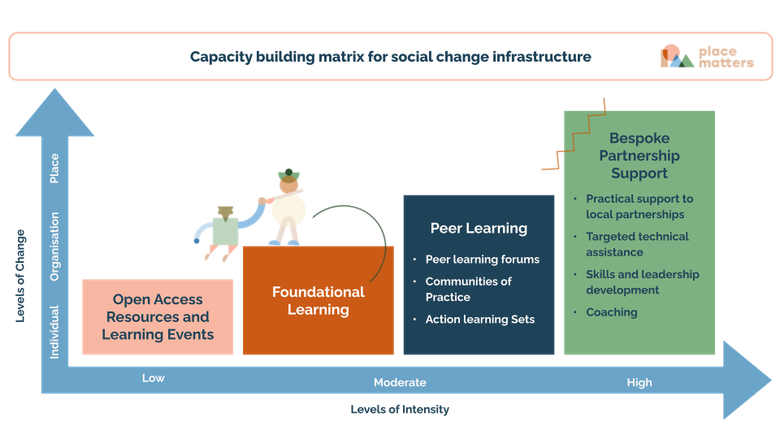

We see four main approaches to building this capability:

A shared understanding of practice: The field of place-based practice remains relatively immature in the UK, with limited points of reference for excellent practice, and competing narratives and tools. We need a common language and framework that builds on successful examples, allowing for distinctive approaches while building confidence in what works.

Open access learning: Webinars, resources, and case studies build foundational understanding. They're valuable for building baseline knowledge, but are rarely sufficient on their own, particularly for new backbone teams.

Peer-led practice development: Networks and communities of practice that connect places with shared priorities are often the most trusted and impactful sources of support. The backbone role requires unique qualities and skills that are best developed and nurtured through peer development. This is particularly valuable where challenges are strongly aligned, in places with similar characteristics, such as rural or coastal communities, or when tackling similar priorities, such as child poverty.

Intensive partnership support: Learning partnerships that walk alongside collaborations over time, combining coaching, expertise, facilitation, and strategic support. This might include one-to-one coaching for individual change leaders, targeted expertise on specific issues, and practical help that comes from 'walking alongside' a collaboration over its journey.

Most people move between these approaches as their experience grows, starting with foundational learning and progressing to peer networks and intensive partnerships as their practice develops.

A Moment of Promise, and Risk

We're at a critical juncture. Never before have so many place-based programmes been launched at this scale, with such high expectations. The opportunity is genuine and significant, but so are the risks.

If we fail to invest in the skills, leadership, and infrastructure required, we risk repeating past mistakes: well-intentioned programmes that fail to deliver lasting change because they underestimate what it takes to enable communities to lead their own transformation.

If we get it right, we leave something more valuable than any single programme: confident communities with the capability to shape their own futures. Communities that don't just receive funding but also have the infrastructure to use it effectively. Communities that don't just respond to change, but drive it.

As Locality put it in their report Community Powered Neighbourhoods: 'Devolution can't just be about the public sector letting go; more important is that we support communities to power up, so they can instigate and drive improvements and change in their own neighbourhoods themselves.'

This requires all of us, funders, delivery organisations, advisors, and communities themselves, to come to this work as learners. To be honest about what we don't know, generous in sharing what we do know, and committed to building the infrastructure that makes lasting change possible.

The question isn't whether communities can lead change. The question is whether we'll invest in the infrastructure they need to do it well.