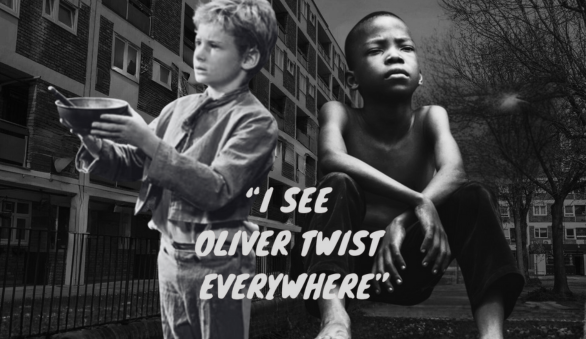

‘I See Oliver Twist Everywhere’: Stories, Data and Power in Northumberland Park

Acknowledgements

With thanks to the residents of Northumberland Park who have shared their stories, to Olivia Opara, who put forward the ‘Oliver Twist theory’ that forms the basis of this piece, and Darius Corrigall for the deeper data analysis he provided to explore persistent patterns of class-based inequality in Haringey.

Introduction

Stories Set the Hypothesis: Race, Child Poverty and Place in Northumberland Park.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved stories. As a child on camping trips in Botswana, I listened to elders tell tales around the fire - sometimes again and again, each with its own purpose. The terrifying legend of Rra Selepe, a local axe-murderer said to haunt our campsite, wasn’t just there to scare or entertain us as pre-teens; it bonded us tightly as a group and, I suspect, helped enforce the quiet “rules” of our little collective so we wouldn’t try sneaking out of our tents in the dead of night. Other stories, like Rudyard Kipling’s “How the Leopard Got His Spots,” came to me in the safety of my bedroom as my father read at my bedside. Those tales served a more philosophical and instructional purpose: to impart wisdom about adaptation and survival in a harsh world - albeit through a very colonial lens I only learned to name some years later. Still others were spontaneous and informal: elders’ laments over tea that carried memory, named loss, and sometimes opened small doors to collective healing and joy. Whether cautionary, pedagogical or communal, stories have always been part of the social fabric of my life: a way of saying what we know, feel and believe, and why it matters.

One of my favourite parts of research is storytelling. It’s easy to get pulled into treating large-scale quantitative systems data as inherently more rigorous, important, or objective, and to dismiss the stories people tell as anecdotal or somehow “less than”. But storytelling has existed for millennia for a reason. Humans use stories to warn and to celebrate; to pass on survival strategies; to bond; to communicate hierarchy and social positioning; and to make critiques or engage in politics in less direct ways that carry weight, or are more likely to stick. In the African oral tradition - and specifically in Botswana, where I grew up - poems and stories are often shared by young people in kgotlas - communal spaces where conflict is resolved and civil matters debated - precisely because 'story' and artistic modes of presentation can be less threatening, and more palatable, than direct confrontation with elders who hold greater power on high-stakes issues. In this sense, story can also be seen as a method for political engagement - simultaneously pedagogy, archive and strategy. Stories remember, protect and travel, and crucially, they often persuade where data alone cannot.

I’ve carried this love and understanding of story into my work as a qualitative researcher, and it sits at the centre of how we tackle community research at Roots & Rigour, and approach the use of creative media to tell individual and community stories through our sister company, AiAi Studios. Stories do things: they make experience legible - to the wider world and to those who look like us; they ask to be seen, understood, heard and validated. Sometimes we tell them for affirmation within our own communities; sometimes we tell them to move people who look nothing like us - and who may hold far more power - towards action and change. In recent years, there’s been a welcome turn to lived experience as one response to epistemic injustice - the cold reality that the stories of marginalised groups have so often been missing from official canons of knowledge.

Northumberland Park: how the room began to speak

The recent turn towards lived-experience storytelling has been especially significant in our recent collaboration with residents of Northumberland Park. From the moment we began, I was highly attuned to the kinds of stories people chose to tell - and how those stories were used for sensemaking alongside the large-scale systems data the Just Knowledge team brought into the room.

Over our time together, many stories were told - a number of which my colleagues Celestin and Jolyon have already written about in the two earlier blogs that form part of this series. From as early as our first session’s opening activity, as residents reflected on how they defined and understood “child poverty”, subtle stories began to surface about how residents relate to the place they call home (Celestin’s blog). Because we were still building trust, they arrived first as fragments: quick sketches of ‘the strip’, where locals hang out and sometimes work out; snapshots of daily life seen through anecdotes of local food banks or substance abuse at ‘the hostel’; and, perhaps most charged, the recurrent tales of travel disruption, Cowboy Carter tour-related event chaos, and laments of false promises and abandonment connected with White Hart Lane, Tottenham Hotspur’s stadium, on the edge of the estate (see Jolyon’s blog for a deeper dive).

“It’s disruption. It’s just too much… we have to rearrange because of the concert… the roads will be closed.”

These weren’t random anecdotes. Layered with Celestin’s memories of growing up in Northumberland Park, they began to fix the boundaries of place, signal continuity and change over time, and offer a fuller, richer account of local experience - one that quantitative data alone might never fully capture.

"Oliver Twist" as a working theory

One especially strong example of story in our work emerged in our very first session. It bridged time, race and class; it invoked the memory of ghosts of the past and those who came before; and it pointed to longer-standing continuities than I had imagined would emerge before we began. When we asked the group to draw and then explain what “child poverty” meant to them as part of our grid elaboration activity in session one, Olivia Opara, said this:

“When I think of child poverty, I hear a child. And when I think ‘a child’, I think… well, I know it’s set in Victorian times, but even though it’s centuries ago, it’s still very much the same… So I think about the same issues as the ones faced by Oliver Twist. And Oliver Twist is about an orphan who lives in London, and him and other orphans, they are basically exploited by this man who sends them running through London to chimney sweeps, and they barely get anything [for their labour]. And, in a way, [the story is] echoed in what happens today. Even with the route running and county lines, and stuff like that. It’s very like Victorian times, like the 1800s, yeah.”

The power of a familiar story is that it creates a shared knowledge base and a quick route into analysis. So when Olivia called upon the well-known story of Oliver Twist, it exposed a dynamic we needed to delve into: how the exploitation of children in Victorian workhouses resonates with contemporary patterns of youth exploitation and coercion, including county lines, in and around Northumberland Park.[1]

This wasn’t a one-off reference. We returned to Oliver Twist session after session - so much so that I half-jokingly started calling it our ‘Oliver Twist theory’. As Olivia kept reminding us, Oliver Twist was everywhere - and her theory was worth testing as part of our ongoing data work.

Olivia: “I would say [if you want to gather more data or test out some hypotheses], to... look at how the class system was the same [in] Victorian times, like the 1900s, [and] compare that to how the class is now. And then compare the level of child poverty then to child poverty now. Just to see. Because I kind of think that the UK is stuck in late Victorian ideas, you know. The system is stuck. I mean, that’s why the class divide is moving the way it’s moving, and that’s why we still have this, the type of poverty that’s about the scene. It just has a different face.”

Tamanda: “You are going to coin and write a book about this Oliver Twist thing….” [laughter]

Olivia: “It is like Oliver Twist, though. Because I still... I remember reading that book in primary school. And you were like… [looks around and shrugs]. We could [see it everywhere]. We had discussions about it, and we could all relate to Oliver Twist. And that was when I was like, 10, and now it’s still [the case]… like, I can still see Oliver Twist all over the roads. I see Oliver Twist everywhere.”

Testing the Oliver Twist story–theory

As you’ll see, our light-hearted exchanges about coining an ‘Oliver Twist theory’ contained a truth. In our second workshop (which Jolyon describes in his blog), we examined a map of Haringey that starkly illustrated the east–west class divide and long-standing wealth inequalities. Later, Darius extended our thinking, sharing some research he’d done on local history between workshops, and showing why the Oliver Twist frame had real analytical merit. As part of his exploration, Darius traced the east–west divide back to late-Victorian development. Housing here was “built around [rail] lines,” with the eastern route running to the Docklands and offering cheap workmen’s fares on the old steam trains. That pricing made it possible to “commute from Tottenham down to the Docklands” for docker jobs at a time when London was smaller and East-End slums were overcrowded; people moved out to new, rail-served suburbs and into larger homes. He pointed to Noel Park as a philanthropic, rail-oriented estate shaped by those fares[2], and to Booth-era maps (c. 1930) that show Muswell Hill/Crouch End/Highgate as largely middle or upper class, and Tottenham as predominantly working class, with the poorest streets later replaced by post-war social housing[3]. In short, what he was able to drive home was this: transport corridors + speculative building + labour markets had laid down classed geographies more than a century ago, and those patterns continue to echo in Haringey today, helping to explain why risk and exploitation tracked along the same routes, and why a resident reaching for Oliver Twist wasn’t so much nostalgia as analysis. In other words, Olivia’s deployment of the Oliver Twist story seeded a hypothesis; and the history and data started to corroborate it. Or, to put it another way: Stories are not ‘nice add-ons’; they are how communities set the research agenda. And how they make sense and generate theory about where they live, and what happens in that place

The Significance of Story: What Adler's Framework Helped Me Name

Listening to one of my favourite podcasts recently - Hidden Brain with Shankar Vedantam - social psychologist Professor Jonathan Adler gave me a useful framework for making sense of what was happening in our sessions. Adler’s work suggests three things that felt immediately relevant: (1) people can hold multiple, even contrasting, stories about the same issue or place; (2) stories operate at three levels at once - individual, interpersonal, and collective or 'cultural'; and (3) how we tell stories reveals a lot about power, since storytelling can be about countering more dominant and powerful 'master' narratives offered by people in positions of greater power.

In Northumberland Park, we saw all three levels in motion. At the individual level, residents tried out language for hard chapters: the horror and helplessness of what felt like a “stuck,” incurable, unending - even inevitable - situation, with people feeling abandoned and let down by both the Tottenham Hotspur Football club and the council. Alongside this sat George Osborne-esque “bootstrap” arcs - ‘work harder’, ‘get educated’, ‘start a business’, ‘get out’ - that felt true to how some of us have been taught to survive, but ran headlong into more troubling data and lived experience reflections, which revealed that many young people remain poor despite relatively strong attainment in the local area. At the interpersonal level, meaning shifted in dialogue: we drew, spoke, listened, then returned to the same touchstones - Oliver Twist, the community, the Council, the stadium - until a reference became a set of working theories we could interrogate together.

Perhaps most importantly, at the cultural level, a common and powerful thread was the way in which residents offered counter-stories to the polished master narratives of borough-wide uplift, including widely asserted claims from both the local authority and Tottenham Hotspur about the positive impact of the club and its creation of employment and other economic benefits for local business. Seen through Adler’s lens then, the group wasn’t asking for a quick redemptive bow; they were doing the slower work of meaning-making - what Adler calls ‘exploratory processing’ - as part of an attempt to rewrite the cultural story from the bottom up.

Conclusion: Power, accountability, and the messy question of what's next

As we approach the end of our work in Northumberland Park and the launch of our report and public webinar, we eagerly await a formal response from Tottenham Hotspur Club and the local authority to the early, private draft of findings centred on residents’ voices. It remains to be seen whether the master narrative of borough-wide uplift - the seductive redemptive arc of a stadium that is “net positive” - will be held fast as part of a standard PR response, or indeed whether institutions will stay open to bottom-up counter-stories and work with residents to pursue meaningful change.

Our own research and digging into the club and foundation's annual reports, and efforts to speak with local councillors have revealed that much of the master narrative of uplift rests on macro rather than highly localised data relevant to Northumberland Park - for example, the Spurs Foundation's latest impact report launched at the House of Commons, and the Club's 2023 socio-economic contribution study which are both in the public domain, refer to broad borough/London macro benefits rather than granular or Northumberland Park-disaggregated data or evidence of change. One possibility is that scale here functions as a shield, masking the reality of life for some of the youngest and most deprived residents of the borough by moving the conversation away from Northumberland Park. The effect of this is predictable, amounting to a flattening of place, blurred accountability, and a sidestepping of youth-level impacts; “We help Haringey” becomes the alibi for “we won’t show Northumberland Park.”

This is a project about stories, data and community power led by young people in a place living with high deprivation and limited leverage. That matters for how we will likely read any response and gaps in data. Without Northumberland Park-disaggregated evidence (on programme reach, jobs, procurement, and disruption), young people and residents cannot contest institutional claims on equal terms. One immediate thing we might hope for, should club and council be willing to partner for positive change, would be a commitment to ensuring better data and units of analysis. In that respect, our hope is simple: match the scale of the claims with the scale of the proof, and make space for residents - especially young people - to help shape the questions and co-interpret what counts.

Let me end with three plain statements that follow from the work:

- Power shows up in who chooses the unit of analysis - and who controls the evidence.

- If the benefits of the stadium are borough-wide, but the burdens are local, equity demands local proof.

- A right of reply is welcome. A right to overwrite residents’ accounts is not.

What happens next is, in part, up to the Club and the Council. Hold fast to the master narrative, or meet these counter-stories with place-level data and a willingness to share interpretation and action that can genuinely create change? Northumberland Park deserves the latter.